How to Be Good

A Brief Commentary on “Sensitive Guys” and its Implications

February 26, 2019

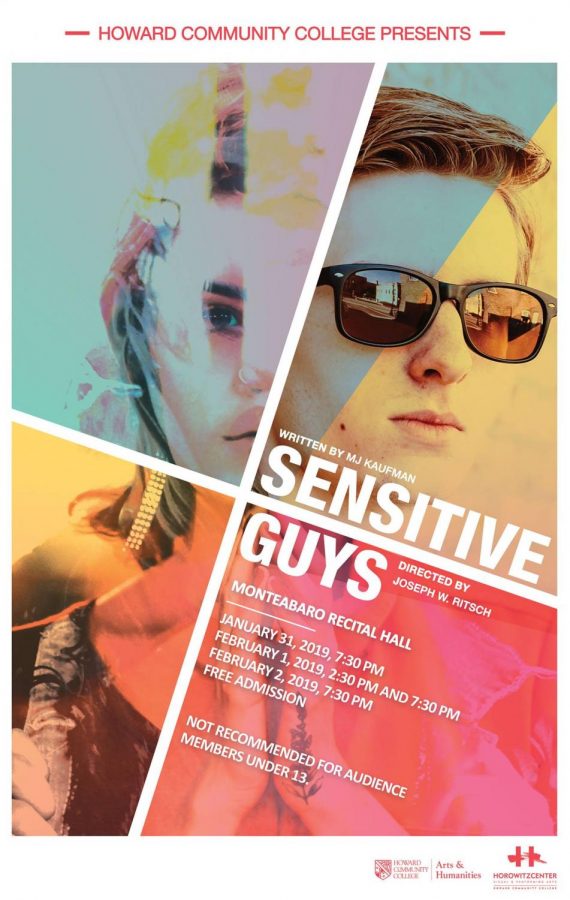

The Howard Community College Theatre Program recently performed the play Sensitive Guys, a timely and poignant commentary on masculinity, consent, and misconduct written by MJ Kaufman and directed by Producing Artistic Director of Rep Stage, Joseph W. Ritsch. Fittingly, Kaufman’s nuanced depiction of the struggle to establish and maintain personal morality and meaningful relationships at the fictional Watson College was enacted by a quintet of HCC student-actresses: Courtney Gingliano, Jordan Stanford, Sierra Young, Aly Tu, and Madeleine Kline, each playing multiple roles – and multiple genders.

While it would have been easy to snort and chuckle at the often comically stereotypical portrayals of the male characters, the painfully relevant – and devastatingly familiar – situations presented by each successive scene sent a serious message that was hard to ignore. In an early scene, Kline, as Will, enters the Watson College Men’s Peer Education Group (read: how to treat women right and be a better man), asking one of the quintessential questions of the drama: “What’s the trick to being a good guy?” The events that follow provide more of a checklist of what not to do than any actionable answer.

Leslie (also played by Kline) approaches first a College Dean, then the Survivor’s Support Group – a ladies-only affiliate of the men’s group – seeking aid in the aftermath of her assault, but uncertain what form that help might take, and burdened with the knowledge that her attacker is a member of the Men’s Group. The Dean, played by Tu, is perturbed by her story, but not motivated to help. As a woefully recalcitrant mandatory reporter, he refuses to handle the situation properly, instead suggesting Leslie should take time away from school – nevermind that she is the victim, or that her academic and social life is at stake. As remarked by Valerie Lash (HCC’s very own Dean of Arts & Humanities) during the post-show talkback, Tu’s Dean is an example of how faculty should not respond to allegations of misconduct, regardless of their caution or uncertainty. No one wants to be in such a situation – least of all the victim – but when it happens, we have to confront it.

Kline’s spine-tingling account of her assault is a shining example of how drama transcends the stage to occupy a very real, very necessary role in our lives. It may be staged, but this is real; we have all heard this story. As Tu revealed during the talkback, the key for each actress to step fully into each character was “reminding ourselves these are real people.” How true.

To recount the many stellar moments of the play would require another article, so I will hit the bright spots: Tu’s hysterically accurate ‘bro’ mannerisms as Pete; Young’s incredible impetus and verve, especially as aspiring good-guy Jordan during the argument with Stanford’s Tracey; Stanford, delivering a spot-on monologue as the self-entitled Tyler; Kline, as mentioned; Gingliano, in the final scenes, as the remorseful – yet guilty – Danny, president of the Men’s Group.

Read that list again. What is wrong with it?

It raises the question: where are the women as women? Such is the very danger this play warns us about: men can be louder, take up more space, speak over women, and have easier access to roles of power. By their very presence they can be more obvious. Perhaps I am simply chilled by the eerie accuracy with which the actresses slipped into that masks of masculinity, even though the most fixating, haunting, and compelling dialogue was delivered by the female characters, especially during the grievance circle, where each member of the Survivor’s group recounts a disturbingly recognizable tale of a recent unwelcome encounter.

The play reminds us that men, regardless of whether they are ignorant, enculturated to indifference, or ineffably indoctrinated into the cult of ‘toxic masculinity’, are still responsible for their own behaviors that minimize and victimize women. (For more about male psychology, see the American Psychological Association link at the end of this article.) To understand some of these issues as they might occur on our campus, I turned to one of HCC’s newest staff members, Christy Lee Koontz, Associate Director of Conduct and Compliance & Deputy Title IX Coordinator.

Koontz, located in MH 119, offered a few key tips for students. First and foremost, she wants students to know that her door is always open; she encourages students to come talk to her for any reason, especially if they have concerns about student conduct, whether sexual or otherwise. She is the nexus of mandatory reporting at HCC, meaning that she gets to decide to do with any information that comes to her, but may not be required to report to anyone else; she will always do what she can to protect all persons involved, though she also has obligations to campus safety. She added that any information shared with a counselor is confidential. (Professional counselors are available to students – visit RCF 302 for more information.)

Regarding consent, Koontz explained that students should be aware that sex, and relationships in general, are all about communication. Communication is important not only for social and personal reasons, but for legal reasons; to meet the prescriptions of federal law, consent during a sexual encounter must be affirmative and ongoing. This means that consent must be given at every step of an intimate encounter, and that consent can be revoked by any person, at any time, for any reason.

Leaning on her background in the psychology of decision-making, Koontz advises students to think

twice before they act. Koontz says, “90% of the ‘decisions’ you make every day are on a predetermined loop” – such as they way you walk to your car, the steps you follow to make breakfast, and so on. We are constantly receiving signals that we need to make a decision, and listening to those signals takes effort; to save energy, the human brain evolved to automate as many processes as possible. It is easy to go through our day without really focusing on the signs that are telling us we should do something different; it is more convenient to just do what we want. If you find yourself making decisions by taking the path of least resistance, Koontz asks: “Have you figured out how to navigate the consequences?”

All actions have consequences, and some actions – like not seeking and attaining consent – can have massive consequences. So when it comes to important moments in your life, such as intimacy and asking for consent, pay attention. Look for signals that might be telling you you need to change your behavior – your partner’s body language, facial expressions, and dialogue in particular. And don’t try to manipulate your partner into giving consent – coercion is grounds for sexual misconduct. Accept that your partner may want something different than you. The world won’t always align with your desires; accept that and learn to adjust your expectations, behavior, and decisions, and you will find yourself that much closer to being “good.”