The Emotional Impact of Two Tragedies: Remembering 9/11 During the COVID-19 Pandemic

An examination of the core differences between 9/11 and the COVID-19 crisis

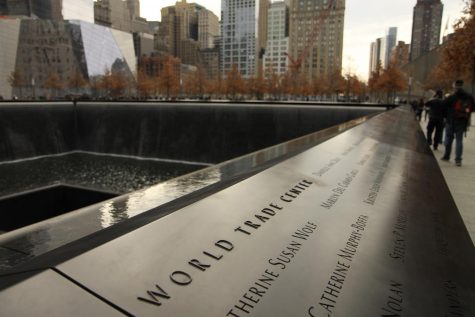

The One World Trade Center now stands in New York City.

September 11, 2020

Nineteen years ago on this day, the American people were shaken to their core when a plane careened into 1 World Trade Center, only the first of several hijacked aircraft to hit their target that day, resulting in the death of 2,997 people. The tragedy will undoubtedly remain in the American psyche for decades to come, but that legacy is defined just as much–if not more–by the way our nation united in collective grief for the lost. An emotional force so powerful, that American flag manufacturers had to triple production, that presidential approval ratings surged to an all-time high at ninety-two percent, that it sparked an objectively horrific war in Iraq. It was a cultural reset: music, art, and books all born from the grief and pride of the American people.

Flash forward to the present when the United States is in the midst of a global pandemic in which over 190,000 Americans have lost their lives, making it more fatal than the 2001 attacks by a factor of 64. One would imagine there to be a similar and yet greatly intensified swell of emotion spanning the nation, and yet, this is simply not the reality. While 9/11 dominated political discourse in the years following the attack, six months into lockdown Google Trends data shows a startling decline in queries related to the virus, revealing disinterest even as the pandemic becomes more deadly. The question that then arises is: What circumstances are to blame for this glaring disparity? While there are innumerable factors in play, the simplified answer is that the Coronavirus crisis lacks two powerful elements: tangibility and a common enemy.

Traditionally, the term “tangible” refers to an object that takes up space but is also more broadly used to describe events or ideas that are clear-cut and easy to process. There is a dramatic difference between the tangibility of the coronavirus crisis and the 2001 attacks. The horrors and narrative of the 9/11 disaster itself are gripping and overt— for weeks after, images of the smoldering Twin Towers were plastered on every magazine cover and any American could watch clips of the aftermath. When you think of 9/11, you think of visuals, of New York, of the Pentagon, of Flight 93. The tragedy had a defined setting and progression which, in turn, allowed people of all backgrounds to comprehend it in a very raw way.

On the other hand, COVID-19 is completely intangible–the virus wreaking havoc on our population is too small to see with the naked eye, an invisible threat. The victims themselves are sequestered away in hospitals or their homes. This means that for those who have not lost loved ones to the virus, neither the “attacker” nor the “victim” of this tragedy are before their eyes, making it easy for the gravity of the situation to be underestimated.

The second thing that separates the 2001 terror attacks from the contemporary global pandemic is that while the former has an objective perpetrator, the latter does not. The emotional significance of a common enemy is that those affected will rally together as they collectively direct their anger towards that enemy. This can create a community or potentially a movement, both of which extend a tragedy’s legacy and imbue it into a culture. The involvement of Al-Qaeda in 9/11 and the subsequent rise in American nationalism is a textbook example of that phenomenon.

The reason why COVID-19 is different is that it’s a virus that’s directly killing people— and a virus doesn’t make a good villain. Instead of anger and grief translating into unity, without an undeniable common enemy, discourse around this pandemic has become a subjective blame game. Some groups blame citizens who choose to throw parties, some blame the president for a muddled message and poor leadership. Others blame China, or local governments, or Republicans, or Democrats, etc. This conflict ultimately leaves many with a sense of overwhelming exasperation, subsequently dissuading the population from monitoring the news cycle, therefore pulling attention away from victims.

On September 11, 2020, Americans dwell in the shadow of one tragedy while also in the midst of another, and comparison is inevitable. In a year defined by disorientation, stepping back to relate current tumult to past landmarks can reframe the seemingly incomprehensible so that we as a nation can process and heal.