In Defense of a Particular Violence

Who Can Riot In America?

June 26, 2020

Riots are the language of the unheard

—Martin Luther King Jr.

I remember my first fight. After my parents’ divorce, my mother and I moved to Cherry Hill, Baltimore to live with my aunt. I was already acquainted with a lot of the kids in the neighborhood from family cookouts, but as a Black boy who had spent most of his life in Howard County, I was bound to be tested.

Most of my days there were spent outside playing games, and anything including games and adolescent boys is going to involve some roughhousing. There was a boy in the neighborhood I had trouble with, and one day, the “roughhousing” escalated to the point of him wanting to fight me. And, well, I fought him. It was nothing like the fights I saw on cartoons or video games; it was a messy, tangled jumble of fists, anxiety, and an insurmountable rage only a Black boy knows. After the two of us were separated and the fight was over, the boy threw a couple of choice expletives at me, but he never messed with me again. My first real confrontation with physical violence had met its sound resolution.

A little over a decade later, I’m sitting here watching videos of the protests on social media. The majority of them are peaceful and a minority are violent. Many started peacefully, and after intervention from police, ended violently. Though they are all in reaction to the death of Black people at the hands of police, there always seems to be a mass media frenzy whenever the protests turn violent. Why?

The American media has a natural affinity for the sensational, so they are a part of a tricky dynamic in that they are drawn to, or even perpetuate through outrage, the same thing they condemn–sensation. Even so, it is deeper than mere sensationalism. The reaction is based less on what people are doing, or why they are doing it, and more on the who. Despite the dominant opinion, there is certainly a case to be made for the defense of people using violence to revolt against an unjust system.

Violence never works. While it is quite ridiculous and debasing to compare the conflict of a boy facing a bully to protesters all over the country and the world fighting against police brutality and systemic racism, saying violence never works is just as inane. Did the Haitian slaves gain freedom from France by preaching love and peace? Did the American patriots gain freedom from British rule by pleading with them for lowered taxes and self-autonomy? Did the American slaves gain freedom from their shackles by simply asking their masters? If violence does not work, why is my name Marcus Chewning and not Kunta Kinte?

To say violence does not work is to play the role of the historical revisionist. It is to say that the European colonizers gained control of the Americas because of nice talks over Thanksgiving dinner–a bald-faced lie. America was born from violence and has propagated it ever since, from the jungles of Africa to the deserts of the Middle East. Violence lives in America’s DNA.

Throughout history, freedom has not been without blood; that is the cruel reality of the world. After the assassination of the nonviolent leader Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4, 1968, there was a week of riots known as the Holy Week Uprising. On April 11, six days after the riots began, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act of 1968. As John F. Kennedy once said in 1962, “Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.”

The two key political leaders, King and Kennedy, would surely denounce any act of violence authored in their name. However, in a sickly ironic fashion, both men were assassinated by a person with a gun or, more accurately, a country whose resistance to change was far greater than its love for so-called peace.

Riots can be quite costly—not only in arrests and personal injury but in property damage as well. Property damage translates into a loss of money and that, in a capitalist system, means a loss of power. And loss of power is the single greatest fear of white supremacists. Riots are ugly and bitter, but it strikes that fear of loss which makes people pay attention to issues they would otherwise ignore.

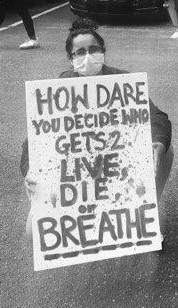

What I am advocating for here is not anarchy or violence without intent or purpose. What I am advocating for is self-defense and survival. The American government cannot require a standard of civility or nonviolence out of its citizens when they have not cared to embrace the same. The social contract is therefore nullified. One cannot respect a government that does not abide by the laws it creates. If it is peace they want, then they should not kill, shoot, pepper spray, tear gas, run over, push, punch, or oppress people for simply using their First Amendment right to speak against a corrupt system.

The same country which seems to have little to no qualms about self-defense or Stand Your Ground laws cannot wrap its head around the idea of a people rising against a system that has perpetually brutalized them. I think I know the reason why.

Violence invalidates the message. In 1786, Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter to James Madison in which he said, “I hold it that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing, and as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical.” By today’s standards, the American patriots of the Boston Tea Massacre would be framed as “thugs,” “terrorists” and “animals” as the protesters of today now are.

Or would they?

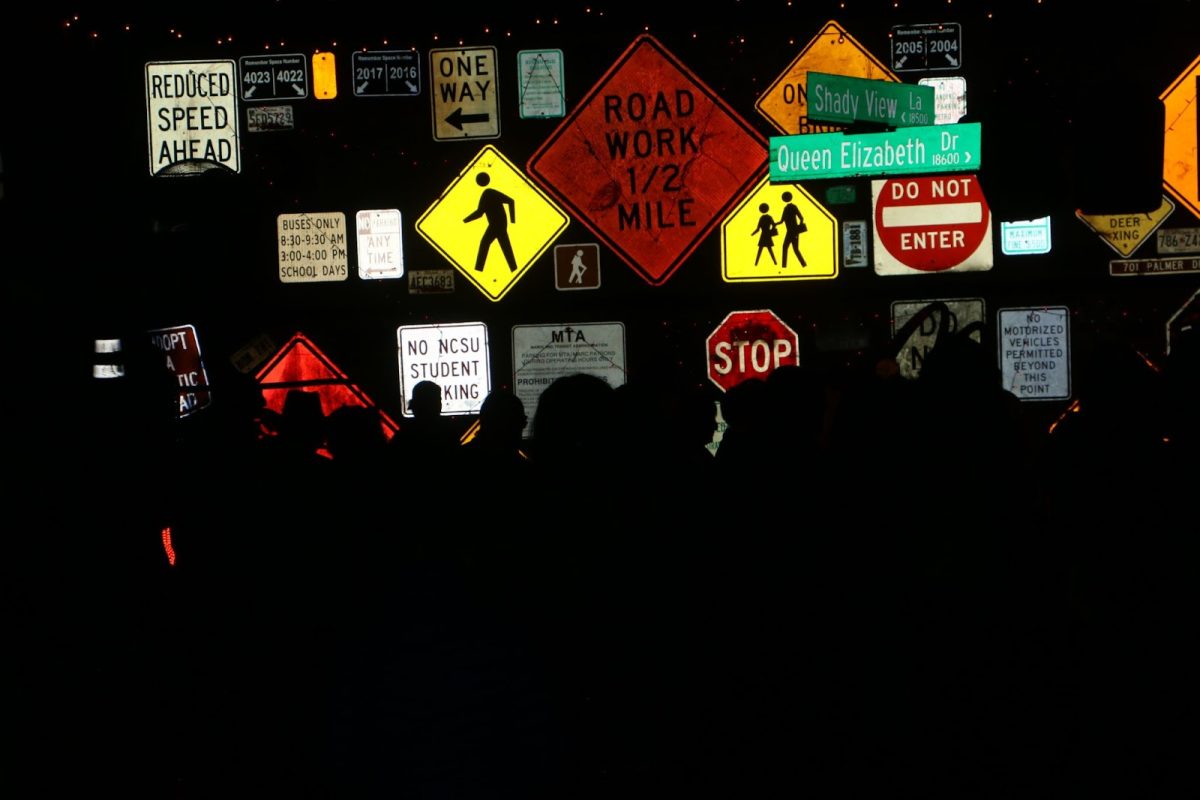

In contemporary life, riots have erupted for small things, like a sports team losing a game, or winning for that matter. America chooses who can be violent and who cannot. It was only a few weeks ago when protesters, mostly white and armed, took to the Michigan Capitol. All happened without pepper spray, rubber bullets, tear gas, riot gear, and Black lives mattering at all.

The country constantly denies the Black person the same privilege to violence their white sibling has long enjoyed because Black people are not, never have been, and very well may never be, viewed as real Americans. The prolific writer and activist James Baldwin once spoke about this color double standard on the Dick Cavett show in 1968. During the interview, he said, “when any white man in the world picks up a gun and says, ‘give me liberty or give me death,’ the entire white world applauds. But when a Black man says the exact same thing, word for word, he is judged as a criminal and treated as one.” History, once again, repeats itself.

When the white person riots, it is labeled necessary because it confirms the American record of white supremacy in a system quite literally built for the whims and desires of white people. When the Black person riots, it is a threat because it goes against the American record of white supremacy.

It is for this very reason that Robert E. Lee, a traitor to the Union, is memorialized through public statues and the names of school buildings, while Nat Turner, leader of one of the most notorious slave revolts, is mostly, but not wholly, blotted from textbooks and the national consciousness. One was fighting for his freedom to control and exploit a people’s existence. The other was fighting for the freedom of his people to control their own existence. But, in the eyes of a racist society, the former is the patriotic hero.

With a more peaceful example, people still call Colin Kaepernick’s peaceful protest of kneeling during the national anthem to protest police brutality an attack against the American flag and what it stands for. Racism is so deeply ingrained into American society that when a person attacks racism, society perceives the person to be attacking America itself.

Violence is not ethical. Violence alone is not ethical, but when a bully is intent on brutalizing their victim, the person aggressed has every right to defend themselves. Asking citizens to be peaceful towards police officers is like asking the sheep to be kind to the wolf pretending to be a sheep, whose sole function in the ecosystem is to prey upon, control, and utterly ravage them. Many will disagree but a force—intent on being violent—only knows and respects what it has been taught: violence.

I will tell you what’s truly unethical: enslaving a people for almost 250 years, effectively ripping away their base humanity, and carrying on in that racist manner from lynching to segregation, and then using the police, modern-day slave patrollers, and the justice system alike to perpetuate a new age of chattel slavery—known as mass incarceration. And to then, without any sort of reparations for past transgressions (to put it mildly), give them a mere, one-time $1,200 stimulus check during an epidemic which disproportionately kills them.

This is happening while the government gives billion dollar payouts to corporations, a gift (I guess) for exploiting American workers every day. Given even a slice of the historical context behind the riots and looting, I cannot see—other than through the lens of an ignorance my Blackness cannot afford—how one can so easily dismiss or misunderstand what is happening today. This stance seems to be the greatest antithesis of ethics. I say, to the bottom of the Bristol Harbor with those brands of ethics!

Such a country, whose founding is rooted in the unprecedented mass looting known as colonization, has no moral basis to stand on in criticizing the looting occurring today. The looting of Native land, lives, and culture, I dare say, is a sin much greater than looting any insured Target or Walmart. It is the epitome of hypocrisy. This country has no right to tell people, whom it has brutalized for oh so many years, that their reaction is invalid, that it is not the right time, that it taints the message.

But do not for a second think that because these historical acts were the sins of your father, or your father’s father, or beyond, that history has nothing to do with you. History is ever-present; it is happening right before you. While you silently reap the benefits of this “unattached” history, it actively destroys me. Your glittering American Dream is my never-ending American nightmare and, while the nightmare is mine today, it can become yours tomorrow.

The Jewish peoples, though discriminated throughout the ages, once thought themselves above the monstrous possibility of a Holocaust—like any rational, empathetic being would—until they were not. If it can happen to one, it can happen to us all. Silence makes the sin yours. If you take nothing else from my writing, take that with you at least.

Nevertheless, our responsibility as people of this country, to save it from itself, is the same. I don’t say this to affect a transient sense of white guilt within you, but instead to be the impetus for enduring, actual change. Being sorry does not accomplish anything. Even if a certain president wins re-election, I doubt most of us are crossing over any neighboring border any time soon. Most Americans–a disproportionate number of whom are Black and brown–are not wealthy. So, as common folk, we might as well make best with what we have and work towards shared liberation. Or may doom enrapture us all?

The chants of “no justice, no peace” are not hollow ones. Black Americans are done asking for a seat at the table; they are demanding it. Though, in the demand of a seat, one admits the ownership of the table. The current table is rather old and reeks of exclusion and elitism; its legs are dilapidated and leans toward the favor of one side over the other. I do not want to sit there. For even if it received a new coat of sheen, the foundations would remain corrupt. It is time for a new table that fits the energy of today. This new table would finally live up to the words written long ago on parchment paper. It would function how a table should, working in the best interest of all and not just the select white and rich few. Besides my personal envisions, there seems to be a place for both approaches in the political sphere.

However, in reminiscing about my first fight I wonder if the boy and I would have talked over our issues instead of fighting, would it have blossomed into a great friendship. I do not know. I no longer needed his friendship, for I had already earned his respect.