What’s in a Glass of Water?

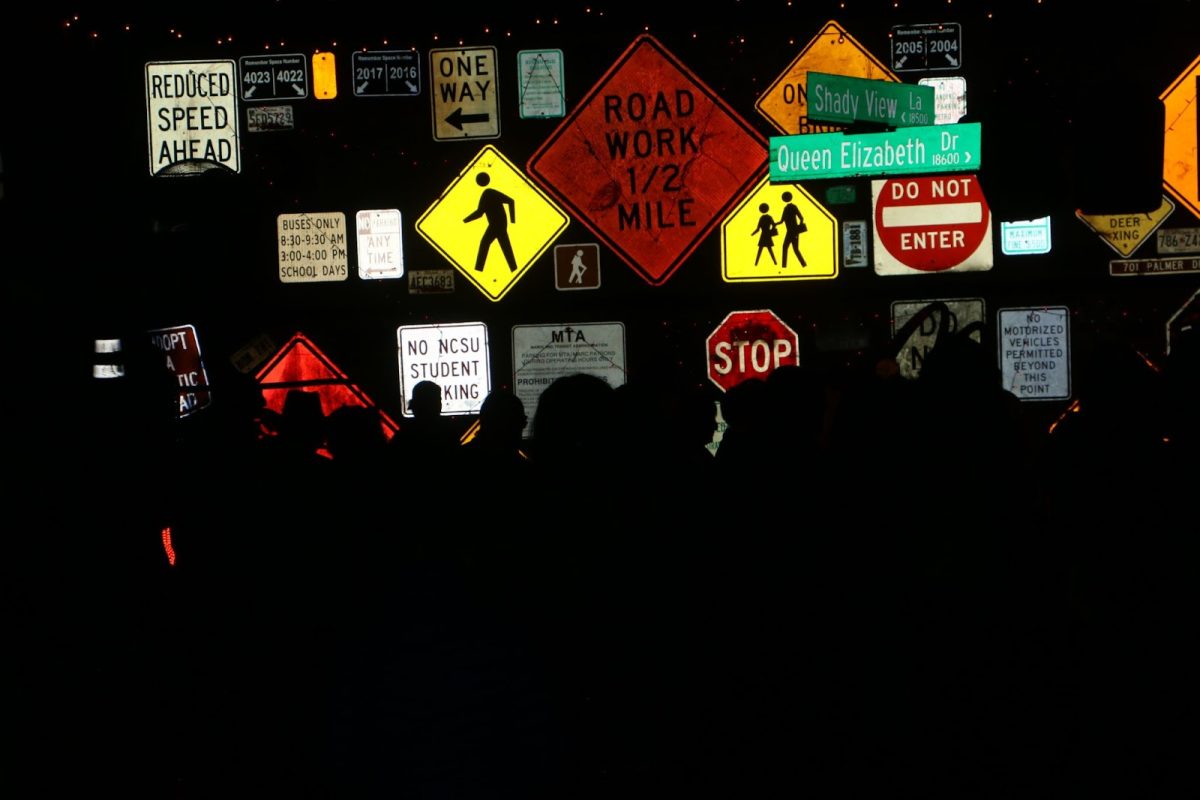

Black and yellow, the universal color scheme for warning and danger, distinguishes signs spanning across entire neighborhoods.

April 20, 2023

Something strange happens every year as the last whispers of winter are whisked away by warm air and golden sunshine. As sleeping plants stir awake and poke their heads through the ground, as bees start to buzz and fragrant flowers begin their blooms, as life itself yawns and smiles at the new season, self-renewing contracts spelled out in terms of death spur large trucks into motion to lawns throughout the country.

Here, the socially sanctioned routine application of poisons to the ground where people walk, children play, dogs sniff and wildlife calls home takes place without the batting of an eyelash. Invisible blankets of chemicals might be sprayed across the surface of entire neighborhoods, with tiny yellow square signs silently sending their startling warning: CAUTION. PESTICIDE APPLICATION. KEEP OFF.

Birds, deer, rabbits, squirrels and all wildlife that share the land cannot read caution signs. How is it to be explained to animals, that under no circumstances whatsoever is it safe to tread on grass after poisons have been applied, that they absolutely must avoid foraging for food anywhere near yellow warning signs?

Animals do not have voices to tell people what routine spraying is doing to their bodies. However, the insidious effects of these synthetic pollutants are documented by science, and ongoingly.

The first intersex fish, which exhibits male and female anatomy simultaneously, was discovered in the Potomac River in 2003, and now they are observed in water bodies all across the nation. Incidences of these abnormalities are directly linked to a chronic presence of herbicides, like atrazine, found in aquatic ecosystems.

Fish are used by scientists as indicator species, which means their high sensitivity to chemical and physical changes in their living environment effectively make them barometers for the health of their habitat—the water. Pertinently, one might draw a connection here and rightly wonder: what does this indicate for humans?

Pesticides and fertilizers are made up of polar molecules, which means they readily dissolve in water. This has enormous implications for the environment. Every time it rains, soluble remnants of lawn chemicals applied to grass get dissolved in rainwater and wash away to the nearest storm drain, stream, or body of water as a form of runoff. That which enters storm drains is simply rerouted, dumping right back out into a river or other water body some distance away—no filtration, no cleaning process, nothing.

It may come as a shock to realize a destination of pesticide-infused precipitation is also the starting point at which water is drawn up to be used in municipalities. In other words, river water tainted with invisible poisons and other potentially present impurities—toxins applied to the grass just outside the front door—is taken up, filtered, and then pulled back through the tap, shower heads, sinks and toilets. As the saying goes, what goes around, comes around.

People are literally contaminating their own drinking water, what they use to wash their hands, shower and cook in! Water travelling across six different states—Maryland, New York, Delaware, Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia—might flow past intake pipes and instead journey into the Chesapeake Bay. As such, paying for the spraying supports the seasonal poisoning of an iconic ecosystem, home to more than 3,600 species that eat, live and breathe in water impurified with lawn chemicals.

Even the washing machine acts as a portal for transport through which chemical toxins travel. Unpronounceable ingredients and secret formulas wash down the drain and end up at wastewater treatment plants where an attempt is made to decontaminate the universal solvent of life—water—before discharging it right back into a river. Different wastewater treatment plants throughout the country vary in their equipment and approaches for treating the daily influx of water to facilities.

Limitations of technology inhibit detection of the presence of many invisible, residual chemicals, while lower concentrations of substances go totally unnoticed. The situation is not ameliorated in the least by the FDA’s laissez-faire approach to chemical regulation. The FDA explicitly states cosmetics and their constituents do not need FDA approval before going to market.

Similarly, food additives (of which there are over 10,000), can circumnavigate the FDA entirely through a process that allows companies to choose their own scientist, conduct their own research, and determine the safety of their own product without governmental oversight. Substances are essentially innocent until proven guilty for indeterminate amounts of time. A plethora of this stuff—indeed an appropriate word—ultimately makes its way to the same place: into the water.

An alternative to detergents, softeners and soaps exists in nature in the form of soap berries, also known as soap nuts. Native to India, the Sapindus mukorossi tree produces berries that have been used for washing, centuries before the advent of commercialized soaps. The berries are not a typical tasty fruit; they release biodegradable saponins which act as a natural soap when combined with water.

Soap nuts—hypoallergenic in spite of the connotation—can be added to a drawstring muslin bag and tossed in with a typical load of laundry for the duration of a wash cycle. Clothing emerges from the washing machine clean, soft and scentless. Happily, using soap berries also tends to be significantly less expensive than laundry detergent.

Steeping soap nuts in boiled water creates a multipurpose liquid with potential to be used as a building block ingredient for any type of natural cleaner. After several uses, the berries begin to break down and lose their efficacy, at which point they can be added to the compost pile. The fruits are anti-bacterial, nontoxic and offer sustainable, safe alternatives to conventional chemicals, with minimal impact to the environment.

The issue of water pollution is of global proportions, the shared responsibility of every single person on the planet. The quality of aquatic ecosystems, of oceans and rivers, lakes and streams, of tap water and the land itself inextricably depends on the choices made by individuals who themselves form small, yet no less significant parts of the collective whole.

Newfound knowledge can serve as the impetus for change.

Contracts can be canceled.