The Role of Equity and Environmental Justice

For much of history, urban development prioritized industrial growth and expansion over environmental and social well-being. Many major cities were built before environmental justice became a key consideration; a shift that only began gaining traction in the 1960s. As awareness of the concerns grew exponentially during the 1960s and 1970s, the concept of smart and sustainable cities gained momentum. However, low-income and marginalized communities have long faced unequal exposure to pollution, poor air quality, and hazardous living conditions, with little say in the policies shaping their environment.

The Environmental Justice movement, which gained momentum in the 1980s, has roots in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, when Black communities fought against racial discrimination in all aspects of life — including environmental conditions. The movement was fueled by the growing recognition that race and socioeconomic status were major factors in determining who lived near landfills, toxic sites, and industrial polluters.

A defining moment occurred in 1982 in Warren County, North Carolina, where predominantly Black communities protested the dumping of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in a landfill near their homes. The protest, while ultimately unsuccessful in stopping the landfill, ignited national awareness and advocacy for environmental justice.

The environmental justice movement emphasized the equitable distribution of environmental benefits and harms. It also highlighted the lack of political power and representation among marginalized communities, as state and federal agencies failed to enforce environmental laws and regulations in these areas. The push for justice led to significant policy changes, including the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Environmental Justice in 1992. However, recent policy shifts have threatened to undo decades of progress.

With many states worldwide turning to smart and sustainable city initiatives, the world is clearly at a turning point. As climate concerns continue to grow and urban populations rise, governments and leaders are actively embracing these strategies to create cities that are not only more efficient but also environmentally responsible. These initiatives are no longer abstract concepts — they are actively shaping the future of urban living.

Impact of Policy Reversals

During his presidency, Donald Trump prioritized regulation and fossil fuel expansion, rolling back nearly 100 environmental protections. His administration’s “drill, baby, drill” approach fast-tracked oil and gas leases on federal lands, weakening regulations on methane emissions — a major contributor to climate change. He withdrew the U.S. from the Paris agreement, reversed fuel efficiency standards, and scaled back protections for nations’ waterways, allowing increased industrial pollution.

Now, under his influence, the National Park Service (NPS) is facing major cuts, with mass layoffs of staff and a reduction in funding for conservation efforts. This move threatens the preservation of protected lands and opens the door for increased industrial exploitation in national parks, reversing long-standing environmental protections. These orders marked a huge step backward, reinforcing the same toxic behaviors and prioritizing industry profits over climate action, which environmental justice advocates have fought against for decades.

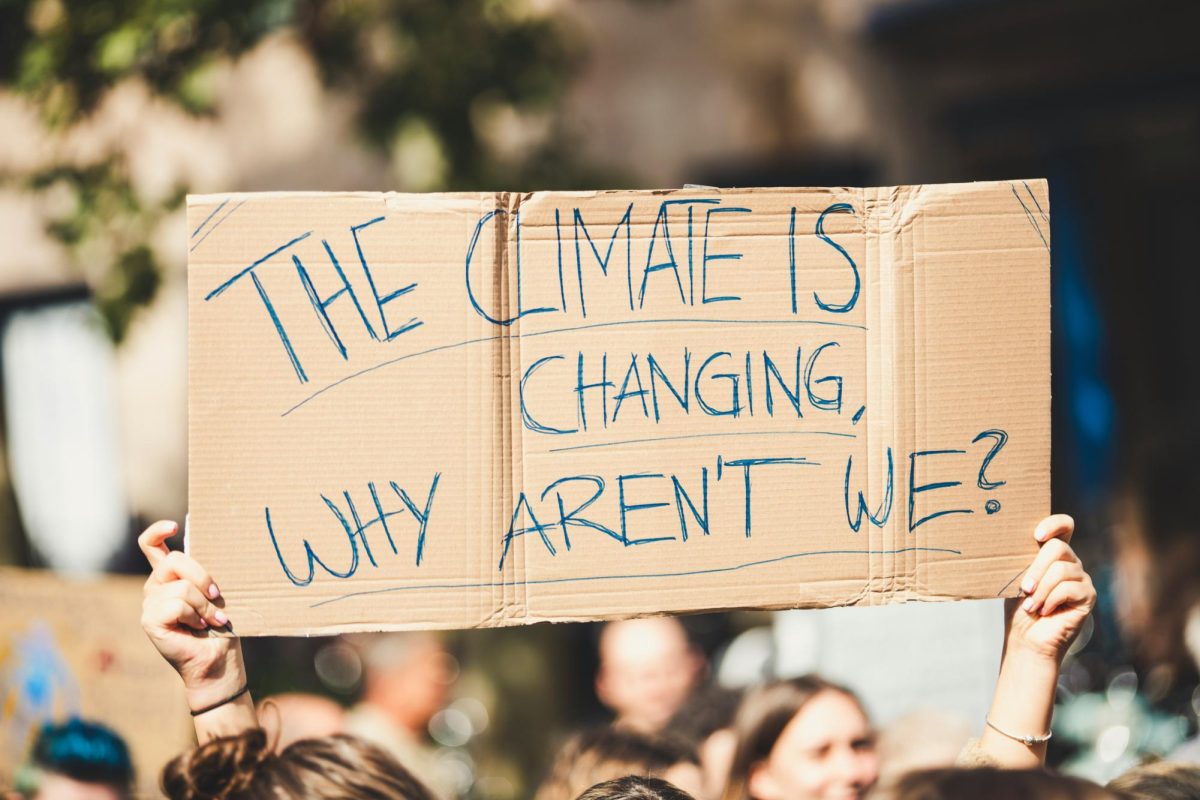

Climate Change vs. Misinformation

Most experts, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, agree that since the Industrial Revolution, human activities have released large amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The Industrial Revolution, which began in the mid-18th century, involved the increased burning of fossil fuels for energy production in factories and homes. This led to large amounts of untreated waste from these factories into waterways and the air, causing pollution. Rapid urbanization was also a key factor due to rapid population growth leading to sanitation issues and increased waste generation.

Concern about climate change has only worsened over the centuries with the continued reliance on fossil fuels and increased population growth. Despite overwhelming scientific evidence, the existence of climate change remains a topic of debate. An article released on Nov. 16, 2023, from The Washington Post discusses an American physicist, John F. Clauser, who won the Nobel Prize in physics for his work on quantum mechanics. Shortly after, he became involved with the CO2 Coalition, a group known for denying scientific consensus on climate change. Clauser referred to himself as a “climate denialist” and stated there is “no climate crisis,” arguing that Earth’s temperature changes are regulated by cloud cover rather than human activity. Climate scientists strongly disagree, pointing out evidence that shows cloud cover is more likely amplifying global warming rather than counteracting it.

Misinformation and confusion prevent us from taking responsibility for the severe consequences we are forcing on our environment, underscoring how misleading narratives can delay climate action and reinforce policies that exacerbate environmental harm.

The Climate Clock: A Call to Action

In New York City, an 80-foot-wide digital climate clock displays the countdown of how much time humanity has left to take action to prevent the worst effects of climate change. As of today, the deadline states four years and 142 days. It is a powerful way to keep us aware and accountable. New York is not alone — similar climate clocks in Seoul, South Korea, and Glasgow, Scotland, serve as stark reminders that the urgency of this crisis transcends borders. No matter how avoidant one remains, the countdown continues. This is not just a warning—it is a final wake-up call. The reality of climate change is relentless, and while individual efforts matter, systemic change is crucial in tackling climate change.

Smart Cities: Technology-Driven Urban Innovation

Smart cities integrate advanced technologies to improve infrastructure, transportation, and public services. These cities focus on efficiency, data collection, and real-time monitoring to enhance daily life and reduce waste. The concept of a Smart City started to emerge in the 1960s and 1970s. One of the earliest examples was in 1974 when the Los Angeles Community Analysis Bureau used computer analysis to gather urban data and inform policy decisions. The bureau used mainframe computers to develop a database of social and physical factors in the city, otherwise known as a cluster analysis.

Smart cities focus on optimizing resource use, reducing congestion, and improving public services through automation. Examples include:

● Smart Traffic Lights – Use AI to optimize traffic flow, reducing congestion and emissions.

● AI-Powered Waste Collection – Sensors detect when trash bins are full, optimizing pickup schedules.

● Smart Grids – Advanced energy distribution systems that optimize electricity use and integrate renewable energy sources.

● Real-Time Air Quality Monitoring – Helps track pollution levels and improve public health.

● Smart Surveillance and AI-Driven Policing – Enhances safety and emergency response efficiency.

Cities Leading in Smart Initiatives

● Columbus, Ohio – Won the U.S. Smart City Challenge and is developing an integrated transportation system using smart mobility solutions.

● San Diego, California – Implemented smart streetlights with sensors to monitor traffic patterns, reduce energy consumption, and enhance public safety.

● New York City, New York – Uses AI-powered waste management and smart grid technology to optimize energy use across the city.

● Tokyo, Japan – Incorporates advanced technology in transportation, disaster preparedness, and urban planning.

Sustainable Cities: Building for a Greener Future

Sustainable cities prioritize eco-friendly urban planning, renewable energy, and conservation efforts to minimize environmental impact and promote long-term resilience. The idea of sustainable development emerged in 1969 when 33 African countries signed an official document addressing environmental sustainability. The United Nations published the Brundtland Report in 1987, which defined sustainable development as fulfilling present needs without jeopardizing the ability of future generations to meet their own. Sustainable cities focus on:

● Expanding Green Spaces – Parks, rooftop gardens, and urban forests improve air quality and support biodiversity.

● Local and Sustainable Food Systems – Urban farming, community gardens, and local food markets.

● Water and Waste Management – Rainwater harvesting, composting, and zero-waste initiatives.

● Reducing Carbon Footprints – Renewable energy, sustainable architecture, and emission reduction.

● Eco-Friendly Transit – Promoting biking, walking, and transportation.

Cities Leading in Sustainability

● Portland, Oregon – Converted 45,000 streetlights to LED, reducing energy use by 66%.

● Detroit, Michigan – Launched an urban reforestation project, aiming to plant 75,000.

● Berkeley, California – Recognized for its strict environmental policies and renewable energy adoption.

● Columbia, Maryland – A planned community emphasizing sustainability through green building, renewable energy, open space preservation, and stormwater management.

● Curitiba, Brazil – Created a waste exchange program benefiting low-income residents.

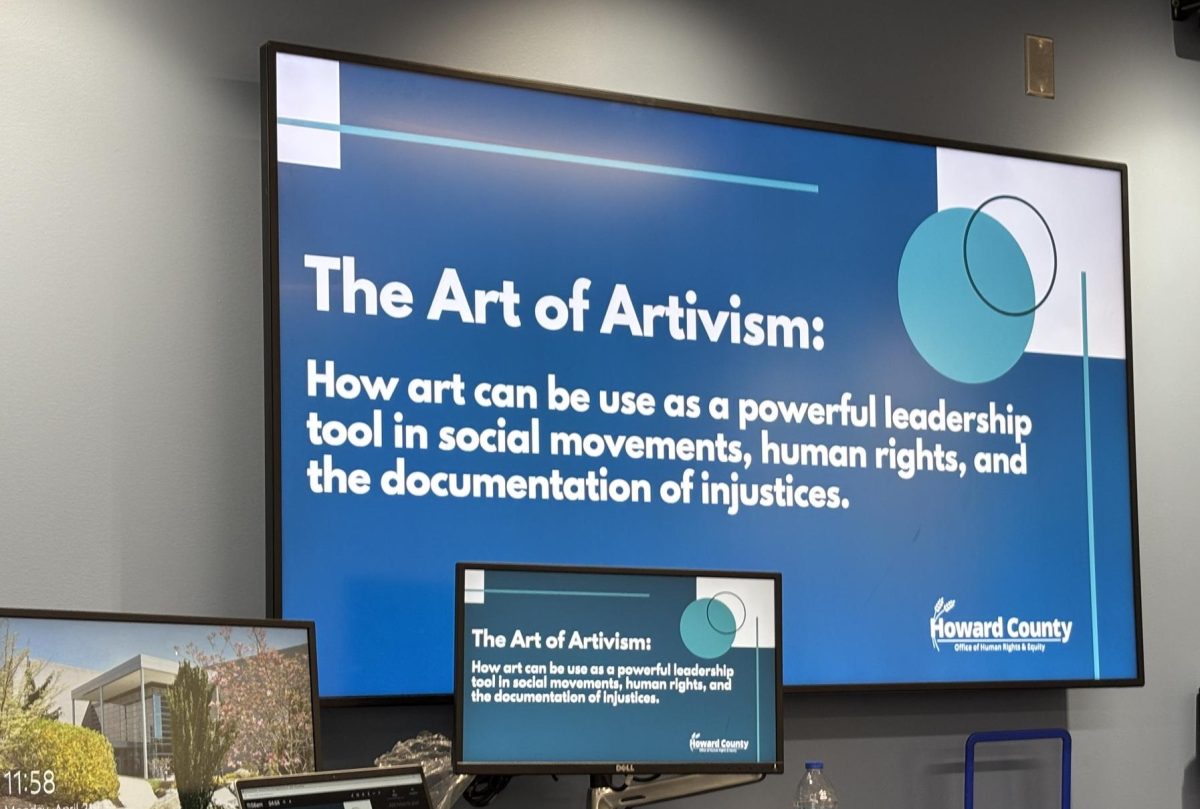

Balancing Smart and Sustainable: Insights from Professor Gretes

While both initiatives aim to improve urban living, they do so in different ways and require distinct methods of implementation.

To gain deeper insight into the intricacies of smart and sustainable cities, I spoke with Dr. Will Gretes, who holds a PhD in Environmental Science and teaches Biology and Environmental Studies. Our conversation delved into the challenges cities face when deciding which model to adopt and how factors like infrastructure, geography, and resource availability shape their approach.

When cities consider the future, the question isn’t whether to be smart or sustainable — it’s about what makes sense for their unique landscape. During my conversation with Dr. Gretes, we discussed how smart cities rely on AI, data collection, and automation, while sustainable cities prioritize environmental conservation and carbon reduction. But is it possible for a city to achieve a balance between the two?

I asked him: “With smart cities relying so much on data collection and surveillance, do you think there’s a risk of losing a city’s human and natural elements?”

Dr. Gretes acknowledged the potential concerns but emphasized that different cities require different approaches. Larger metropolitan areas like New York City or Tokyo may need to lean more towards smart initiatives simply because of their dense population infrastructure demands. However, that doesn’t mean sustainability is off the table. Instead, these cities can integrate green technology into their smart systems – such as AI-powered waste management, energy, efficient, smart, grids, and green roofs – to maintain an eco-conscious balance.

On the other hand, smaller cities with more flexibility may adopt sustainable-first models that prioritize renewable energy, workability, and urban green spaces. Cities like Portland, Ore. and Berkeley, Calif. already serve as examples of sustainable-first urban planning.

Dr. Gretes also pointed out the logistical factors that determine which route cities take. Water, efficiency, energy consumption, and infrastructure limitations all play a role in shaping urban development. While smart grids in major cities can drastically reduce electricity waste, sustainability efforts like solar panel implementation may be more feasible and less industrialized areas.

During our discussion, I brought up the idea of water-powered buildings as a potential sustainable energy solution. However, Dr. Gretes challenged me to consider the sheer volume of water that would be required to sustain even a few infrastructures this way. We also explored solar-powered infrastructure, which is often seen as a gold standard for renewable energy. But then the question arose — what happens when the sun goes down? While battery storage and hybrid energy solutions exist, they’re not always efficient or affordable on a large scale. Dr. Gretes emphasizes that these challenges highlight the need for cities to adopt multifaceted energy strategies rather than depending solely on one renewable source.

Another question I posed was whether smart cities would truly incorporate natural elements if they might fall into the trap of “greenwashing” — appearing eco-friendly while prioritizing aesthetics of real sustainability. He brought up the concept of astroturfing, where artificial greenery is used to mimic natural environments rather than improving biodiversity. The challenge, he explained, is ensuring that sustainability is just an afterthought in tech-driven cities but a foundational part of urban planning.

As our discussion wrapped up, it became clear that the future urban development isn’t about choosing one model over the other — it’s about integrating the best aspects of both smart and sustainable cities while keeping equity, efficiency, and environmental justice at the forefront of decision-making.

What’s the future?

While federal policy has often stalled climate change progress, cities are proving that local action can still drive meaningful change. Instead of waiting for national leadership, urban areas are leading the charge with community-driven sustainable efforts, technological innovation, and policy changes that prioritize people over polluters.

Cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Chicago have transitioned to 100% renewable energy, and over 400 U.S. mayors signed onto the Paris Climate Agreement goals after the U.S. withdrew under the Trump Administration.

Other cities are investing in electric buses, bike-friendly infrastructure, expanding public transport, and banning harmful practices like plastic bags, Styrofoam production, and fossil fuel expansion.

We need cities that are not just smarter, but greener. The most forward-thinking urban centers are blending smart and sustainable concepts — using AI to reduce energy waste, smart grids to optimize electricity use, and data-driven urban planning to address climate impacts in real time. As with all things in life, balance is an integral part of ensuring a sustainable foundation, and the question is not if cities will integrate smart and sustainable elements — it’s when we’ll make visible changes in our environment. Are we the last generation that can fix this, or are we the first to prove that a better future is still within reach?