Who can definitively claim the cultivation of an invention? Many widely used innovations today have origins deeply rooted in ancient civilizations, indigenous ingenuity, or Black culture — yet these contributions often remain miscredited or erased.

The ancient Egyptians, for instance, constructed monumental structures while perfecting beauty routines with clay face masks, kohl eyeliner, and crafting complex wigs. Mesopotamians developed early forms of accounting, laying the groundwork for financial systems. Meanwhile, the Indus Valley civilization cultivated advanced roads and water systems that rival even modern designs.

Colonialism and historical erasure have falsified the narrative and often credit Western societies for innovations they borrowed rather than pioneered. The remnants of these achievements are now viewed through a Western lens, devaluing the ingenuity of the original creators.

People of color have been at the forefront of shaping the world around them. From Ancient African kingdoms developing agricultural techniques, to the extraordinary inventions by African American creators, innovation has continuously emerged from marginalized communities.

Women, in their essence, are natural creators — constantly innovating, nurturing, and shaping the world. Yet, despite their innate ability to develop and nurture, women – particularly Black women – often face the dual challenge of both gender and racial marginalization, with their contributions frequently overlooked or erased from history. In honor of Black History Month and the upcoming Women’s History Month, it’s important to not only acknowledge these overlooked achievements but to celebrate the legacy of Black women inventors whose groundbreaking work has made a lasting impact on industries, communities, and lives.

Dr. Shirley Ann Jackson

Dr. Shirley Ann Jackson was born Aug. 5, 1946, in Washington, D.C., to George and Beatrice Jackson. Jackson’s parents were exceptionally encouraging throughout her educational journey. She attended Roosevelt High School, where she excelled in accelerated math and science programs. Graduating as valedictorian in 1964, she went on to study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), earning a bachelor’s degree in physics in 1968. Jackson continued her studies at MIT under the mentorship of her academic advisor, James Edward Young, obtaining a PhD in nuclear physics in 1973. Her achievement made her the first African American Woman to earn a doctorate from MIT, and one of the first two Black women to earn a doctorate in Physics.

During her time at MIT, Jackson co-founded the Black Student Union playing a vital role in establishing the Task Force on Educational Opportunity, which greatly increased Black student enrollment at the University. After completing her doctorate, she held various prestigious positions, including research associate at Fermilab in Illinois, visiting scientist at CERN in Switzerland, and theoretical physicist at Bell Laboratories in New Jersey. Her research at Bell Labs contributed to major advancements in telecommunications technology, laying the groundwork for innovations like touch-tone telephones, fiber optic cables, solar cells, call waiting, and caller ID. In 1991, she joined the faculty of Rutgers University as a professor of physics, where she taught for 4 years before entering government service.

During this time, Jackson married physicist Doctor Morris A. Washington in 1979, and in 1981 they welcomed their son, Alan Washington. Balancing her personal life with a groundbreaking profession, Jackson continued breaking barriers throughout her career. In 1980, she became the first woman to serve as president of the National Society of Black Physicists. In 1995, President Bill Clinton appointed her to the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), making her the first African American and first woman to hold the position.

In 1999, she became the 18th president of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, the first woman and first African American to lead the institution. She served for 23 years before stepping down on July 1, 2022.

In 2014, President Barack Obama appointed Jackson co-chair of the president’s intelligence advisory board. That same year she, was awarded the National Medal of Science for her groundbreaking contributions to condensed matter and particle physics. Over her lifetime, Jackson received over 50 honorary doctoral degrees, and numerous accolades. In 2005, Time Magazine described her as “perhaps the ultimate role model for women in science.”

Throughout her groundbreaking research, leadership, and advocacy, Dr. Jackson has inspired generations of STEM professionals, particularly women in minorities, to pursue careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

Marie Van Brittan Brown

Marie Van Brittan Brown, a nurse, and her husband, Albert Brown, an electronics technician, lived in Jamaica, Queens, NY. During a time when access to education as a person of color was limited and crime rates in the neighborhood were high, Brown and her husband encountered challenges balancing their long, irregular shifts. Concerned for the safety of their home and children, Albert Jr. & Norma, she designed an innovative security system in 1966 with assistance from her husband.

The “Home Security System Utilizing Surveillance” was an ingenious invention that aimed to address their safety concerns through a combination of inventive features. It included peepholes at varying heights to accommodate individuals of different statutes, a motorized video camera capable of moving between those peepholes, and a monitor that displayed visuals from the front door. The system also features a two-way microphone and speaker for communication with visitors, an alarm system to alert the police in case of threat, and a remote-controlled mechanism to lock and unlock the door. A central control unit allowed for seamless management of the system. Their invention was patented in 1969 and credited for laying the groundwork for modern closed-circuit television (CCTV) and home-security systems utilized worldwide today.

Marie Brown’s invention has influenced a variety of modern technologies and truly reflected her dedication to improving the safety of their community. Her creation stands as a symbol of ingenuity and practice problem-solving, paving the way for the development of more advanced security systems.

Madam C.J. Walker

Sarah Breedlove, famously known as Madam C.J. Walker was born in 1867 on a Louisiana cotton plantation, where her formerly enslaved parents resided. The first of five siblings to be born free, Walker endured poverty, discrimination, a lack of resources, and personal loss throughout her early life. In her early 20s, she became a wife, mother, and widow — life-altering events that ultimately drove her to move to St. Louis in search of new opportunities.

In St. Louis, Walker juggled night-school, her job as a laundress, and active community involvement, including singing in the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church choir and joining the National Association of Colored Women. In the 1890s, she developed a scalp condition that caused hair loss, motivating her to experiment with treatments. These experiments led to the invention of her hair care products, which were tailored specifically to the needs of Black hair.

Her early creations included Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower, a sulfur-based scalp treatment to tackle dandruff and other scalp conditions; Glossine, a heat-protective hair oil for hot tools; and Temple Salve, designed to stimulate hair growth in thinning areas. Her approach highlighted customer education, advising customers to follow a three-step regimen: wash and cleanse, apply the Hair Grower, and style using Glossine and a hot comb.

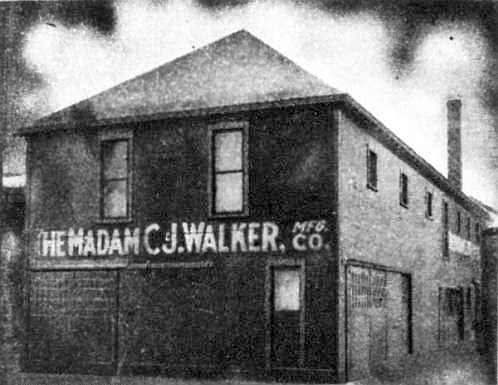

By inventing products that filled a major gap in the Black haircare industry, Walker not only addressed a practical need but also empowered women to take pride in the health of their hair. As demand for her products grew, Walker expanded her business, opening a factory and beauty school in Pittsburgh in 1908. Two years later, she moved the business to Indianapolis and renamed it the Madam C.J Walker Manufacturing Company.

Walker’s enterprise trained thousands of Black women to be sales beauticians, known as “Walker Agents.” These agents earned financial independence, and professional pride, contributing to the overall status of the Black community at a time when systemic barriers hindered economic mobility. Walker used her financial resources to support social causes, fund scholarships, and donate to civil rights organizations.

By her death in 1919, the company had employed 40,000 people and she was the first Black woman millionaire in America. Walker’s hair care line revolutionized Black hair care and set a precedent for empowerment and entrepreneurship that continues to inspire generations.

As a final note, it’s clear that the contributions of Black women are the backbone of so many industries. Their brilliance and resilience have changed the world and paved the way for future generations to build on their successes. Whether it’s Dr. Shirley Ann Jackson laying the groundwork for telecommunications or Marie Van Brittan Brown revolutionizing home security, these trailblazing women remind us that barriers are only problems waiting to be solved. And as for Madam C.J. Walker? She didn’t just build a business — she built an empire that empowered women and gave them the tools to thrive. So, as you’re using your cell phone, locking your doors tonight, and running your fingers through your hair, make sure to take a moment to honor these legacies. Behind each of these great inventions is a Black woman who saw a need, defied the odds, and changed the world — whether history chose to remember her or not.